The Triumph of Henry I

In 1120, King Henry I of England achieved an extraordinary victory: his ruthless cunning and dogged determination had culminated in a highly favorable peace treaty that gave Henry uncontested dominion over the Duchy of Normandy.

In 1120, King Henry I of England achieved an extraordinary victory: his ruthless cunning and dogged determination had culminated in a highly favorable peace treaty that gave Henry uncontested dominion over the Duchy of Normandy.

A mere 20 years earlier, Henry had been little more than the fourth son of William the Conqueror, whose two surviving older sons had inherited the Dukedom of Normandy and the throne of England from their father. In that sense, Henry was the original “Lackland” – a sobriquet assigned to his great-grandson John, born nearly a century after Henry. Henry’s sole inheritance from his father had been a large sum of money.

In the years following the death of William the Conqueror, there was incessant conflict between his two oldest sons, Robert Curthose, Duke of Normandy, and William Rufus, King of England. Young Henry’s allegiance shifted between Robert and William Rufus depending on which brother had more to offer the clever prince.

Just as a tragedy would eventually be the un-doing of Henry’s reign, it was a tragedy that made his reign possible. In August of 1100, William Rufus was killed in a hunting accident. Henry immediately seized the throne of England, claiming that his right to the throne was stronger than his older brother, Robert, since Henry had been born after William the Conqueror became King of England. It was a tenuous claim, but he strengthened it through a fortuitous marriage to Matilda of Scotland, a descendent of Saxon kings.

Just six years later, in September of 1106, Henry had defeated his brother, Robert Curthose, and taken control of Normandy. Robert would spend the rest of his life as Henry’s prisoner.

However, the issue of who ruled Normandy was not so easily resolved. For the next decade, tensions and ever-changing alliances between Henry and the powerful rulers of lands bordering Normandy created a nearly constant state of conflict for the English king. France’s King Louis VI and Fulk V, the Count of Anjou, frequently joined forces against him.

These tensions exploded into full-out war between Henry I and Louis VI, beginning in 1115. Henry refused to pay homage to Louis for the Duchy of Normandy. However, he offered the homage of his only legitimate son and heir, William the Ætheling (an Old Saxon title identifying William as the royal heir). Louis refused this compromise.

In May of 1119, Henry proposed a betrothal between his son and the daughter of the Angevin Count Fulk which included a large sum of money payable to the count. This was an offer Count Fulk could not refuse. He promptly switched his allegiance to Henry, and Louis’ position was now untenable.

Following Henry’s great victory at the Battle of Brémule, Louis formally made peace with him in June of 1120 with terms greatly advantageous to the English King. William the Ætheling gave homage to Louis, and in return, Louis confirmed William’s rights to the Duchy of Normandy.

Following the signing of this treaty, Henry and his seventeen year-old son spent several months traveling across Normandy, securing their holdings and receiving the fealty of the Norman barons.

The Tragedy of the White Ship

By the end of November, Henry and his fleet prepared to return to England, and they were anticipating the celebration of the upcoming Feast of Christmas. At the harbor of Barfleur, a man named Thomas FitzStephen approached the king and proudly announced that his grandfather had piloted William the Conqueror’s ship across the Channel in 1066. Thomas offered the services of his newly refitted vessel, the White Ship, to ferry Henry home to England. Henry politely declined, but suggested that his son, William, and his entourage could take the ship instead.

The sea was calm, and the winds were gentle on November 25, 1120, but the new moon made for a dark night. Loading the passengers took longer than expected, and as the prince and his companions settled in for the 12 hour trip to England, the celebratory atmosphere degenerated into drunken revelry. Casks of wine were loaded onto the ship and offered to both passengers and crew. Some of the more sober passengers quietly disembarked, deciding to find another ship for the voyage. Among those leaving the party early was Prince William’s cousin, Stephen of Blois. He was reportedly sick with a stomach ailment and in no mood to tolerate the wild atmosphere onboard the White Ship.

The captain, Thomas FitzStephen, was an experienced man, and he was thrilled to have the future King of England onboard his ship. He began to boast of the many features of his new ship. The young prince and his friends decided to put the boat to a test. Even though the king had sailed earlier in the evening, William wanted to overtake the king’s ship and surprise his father by arriving in England before Henry.

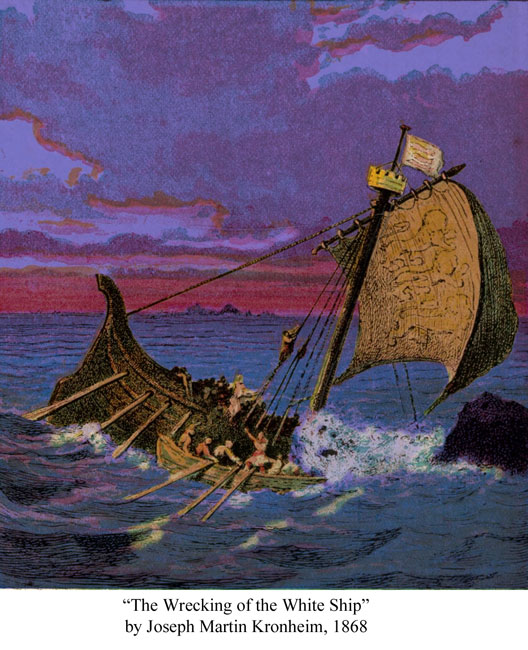

And so it was that a new ship, filled with the elite of its day, began to race across dark, frigid waters in a quest to set a record for a crossing. Like the sinking of the Titanic nearly 800 years later, the White Ship struck a hidden danger in the water – in this case a rock and not the base of an iceberg. The results were nearly the same: a gash in the side of the ship, the rushing of cold water into the vessel, the lack of sufficient life boats (the White Ship carried only one small, extra boat), and the chaotic confusion of passengers and crew alike.

Prince William was quickly ushered into the only lifeboat, and his men began rowing towards the safety of the shore. At that moment, William heard the shrill cry of a familiar voice: his half-sister, one of his father’s many illegitimate children. William ordered his men to return to the wreck to rescue his sister, but the desperate, drowning passengers and crew swamped the small boat carrying the prince – capsizing it and ensuring the death of all aboard save for one man: a butcher who had boarded the ship to collect debts from some of the passengers. He was warmly dressed and was able to survive by holding onto a plank of wood through the night.

Meanwhile, the king’s ship made its way safely across the Channel. Later, some passengers accompanying the king recalled hearing shouts and screams echoing across the dark waters, but at the time they had no idea of the source of this noise. Had they known that a nearby ship was sinking, they could have attempted a rescue. Another cruel parallel with the Titanic.

The Death of Hope and the Birth of Despair

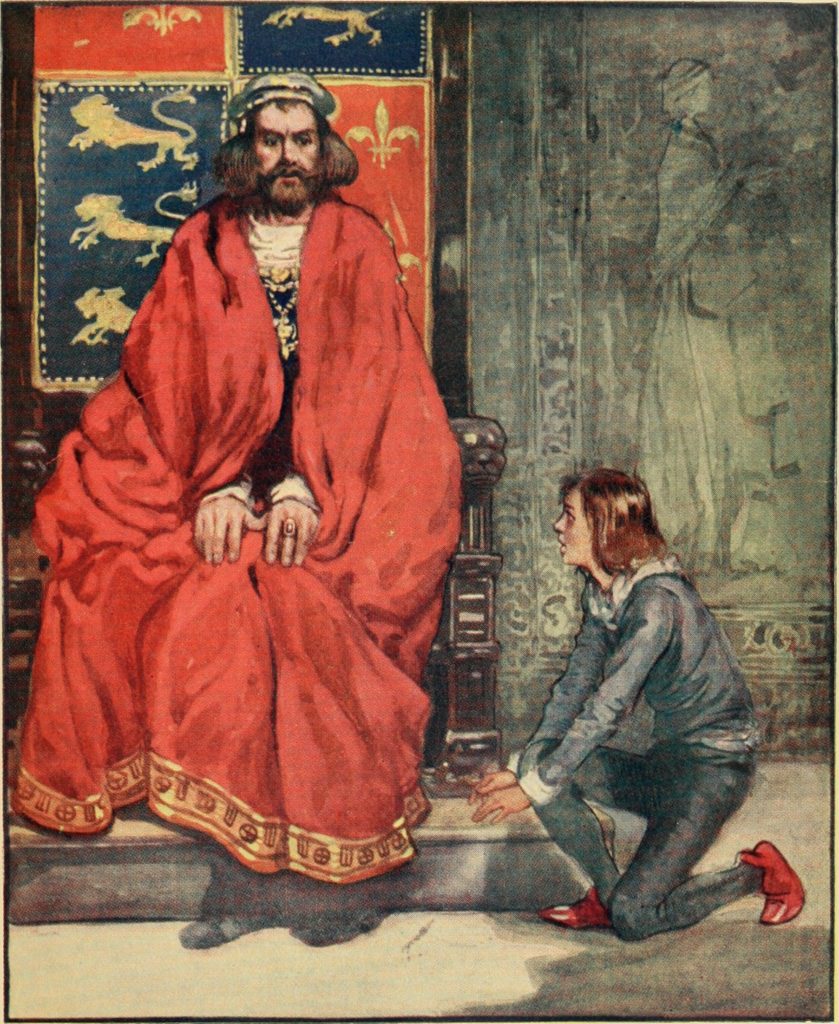

News of the disaster reached England the following day. For two days, the court mourned in private while making excuses to King Henry as to the reason why his son had not yet arrived. Finally, a young boy was sent to the king to announce William’s death. Henry collapsed and was rushed to a private chamber where he was overcome with anguish.

At the moment of Henry’s greatest triumph, when he had finally secured his hold over Normandy, prevailed against the French king, fortified the throne for his son, and ended twenty years of strife, Henry’s legacy and hope for the future drowned in the cold November waters near the harbor of Barfleur. William’s body was never recovered. Henry also lost several of his natural children, all of whom he had loved as well.

At the moment of Henry’s greatest triumph, when he had finally secured his hold over Normandy, prevailed against the French king, fortified the throne for his son, and ended twenty years of strife, Henry’s legacy and hope for the future drowned in the cold November waters near the harbor of Barfleur. William’s body was never recovered. Henry also lost several of his natural children, all of whom he had loved as well.

Few prominent noble families were untouched by the shipwreck, and the next generation of English and Norman nobility had been nearly wiped out. As many as 300 people perished in the sinking of the White Ship. There were 50 crew members, 140 knights, 18 noblewomen, a dozen or so members of the extended royal family, important officials attached to the royal household, and numerous servants. A list of passengers can be found here.

It is said that, during the remaining fifteen years of Henry’s life, he never smiled again. This is likely an overstatement; a fanciful legend passed down through the years. However, as the parent of a beloved, tragically deceased child, any joyful occasion or merry moment in Henry’s life would have been shadowed by profound grief and flavored with the bitterness of regret.

King Henry I had triumphed against all odds: the youngest son had seized the throne of England, captured the coveted Duchy of Normandy, defeated the powerful forces arrayed against him, and negotiated a brilliantly crafted peace treaty; yet, at nearly the very moment of his ultimate victory, all his hopes and dreams for the future drowned in the frigid waters off the coast of Normandy.

The death of William the Ætheling would cause a crisis of succession and result in decades of turmoil as civil war between Henry’s nephew, Stephen of Blois, and his daughter, Empress Matilda, erupted. Peace was finally achieved in 1154 with the ascension to the throne of King Henry II, the son of Empress Matilda and King Henry I’s grandson.

The sinking of the White Ship was arguably the greatest maritime disaster of the Middle Ages. It has been commemorated in several ballads, including this famous poem written circa 1830.

HE NEVER SMILED AGAIN

The bark that held a prince went down,

The sweeping waves rolled on;

And what was England’s glorious crown

To him that wept a son?

He lived—for life may long be borne

Ere sorrow break its chain;—

Why comes not death to those who mourn?—

He never smiled again!There stood proud forms around his throne,

The stately and the brave,

But which could fill the place of one,

That one beneath the wave?

Before him passed the young and fair,

In pleasure’s reckless train,

But seas dashed o’er his son’s bright hair—

He never smiled again!He sat where festal bowls went round;

He heard the minstrel sing,

He saw the Tourney’s victor crowned,

Amidst the knightly ring:

A murmur of the restless deep

Was blent with every strain,

A voice of winds that would not sleep—

He never smiled again!Hearts, in that time, closed o’er the trace

Of vows once fondly poured,

And strangers took the kinsman’s place

At many a joyous board;

Graves, which true love had bathed with tears,

Were left to Heaven’s bright rain,

Fresh hopes were born for other years—

He never smiled again!1Felicia Dorothea Browne Hemans, 1793-1835

1 “The Poetical Works of Mrs. Hemans : electronic version”, University of California, British Women Romantic Poets Project. Retrieved 2017-11-25.

Bibliography

Bradbury, Jim, Stephen and Matilda: The Civil War of 1139-1153, Sutton Publishing Ltd, Great Britain, 2005

Hollister, C. Warren, Henry I, Yale University Press, New Haven and London, 2001

Huscroft, Richard, Tales from the Long Twelfth Century: The Rise and Fall of the Angevin Empire, Yale University Press, New Haven and London, 2016

All images are in the public domain. Modification of public domain images by J. C. Plummer

Text © 2017 J.C. Plummer

Posted on

Most interesting.